Video Alignment

This sub-folder contains code used to manually append metadata to individual video frames, in the best alignment possible to acquired neurophysiological data.

alignVideo Setup

There are three setup steps to run the video alignment:

- Need to have all the video files in one folder, and update the variable VID_DIR in alignVideo.m to reflect that path.

2. Need to have all the .csv files generated by DeepLabCut in order to guess the "best" offset latency between video and neural data, based on cross-correlation between beam breaks and times the paw is detected (and associated probabilities). CSV files are now replaced by _Paw.mat files.

- Need to have all the digital streams .mat files associated with a given video. These should be in the same folder as each other, but can be in a different location from the video files. They should have the same naming convention as the video files (i.e. RC-##YYYY_MM_DD#). These can be in any location, since they are what are selected through the UI if no other arguments are passed to the alignVideo.m function. If they are in the same folder as the video files, then you don't have to worry about specifying VID_DIR.

- (Optional) Include "_Guess.mat" file in the same location as the digital streams .mat files for a particular video. Including this file will skip the initial step where it tries to guess the optimal alignment and can save a couple of minutes each time you load a video to align. Once a video has been scored, the scored output will automatically be used instead of the guess whenever the file is loaded (as long as the file remains in the default output location).

In Matlab, navigate to the videoAnalyses sub-folder in your local cloned repository (or add all folders and subfolders in this path to the current path) and run:

alignVideo;(Advanced) You can specify 'NAME', value input argument pairs instead of modifying the code directly:

- Example 1) specify a different default directory for selecting the _Beam.mat file:

xxxxxxxxxx alignVideo('DEF_DIR','/path/where/mat/files/exist');- Example 2) specify a different directory where video files are stored, and skip the file selection UI:

xxxxxxxxxx alignVideo('VID_DIR','/path/where/videos/exist','FNAME','/full/file/name/of/mat/file');alignVideo Use

File Selection

Overview

HUD

Strategy

Example

alignVideo Select File

Figure 1: File selection. If no arguments are specified, select the Beam.mat file from wherever you have put it. After a few steps of processing, generating the interface, and loading the video, the interface should popup. To skip this step, specify the optional ('FNAME', val) argument pair.

alignVideo GUI Overview

Figure 2: GUI overview. The graphical user interface (GUI) consists of 3 main components: a heads up display (HUD) at the top; the video which is displayed in the middle; and an alignment timeline at the bottom.

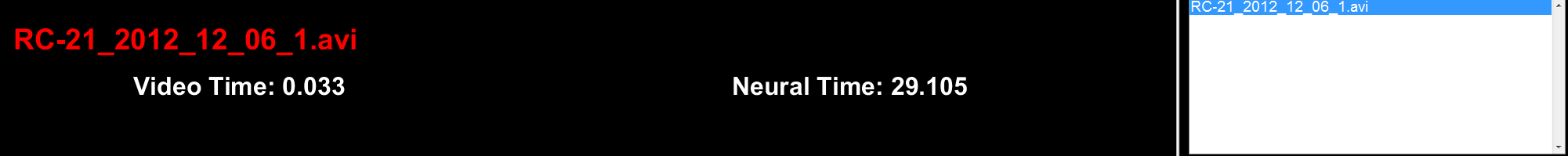

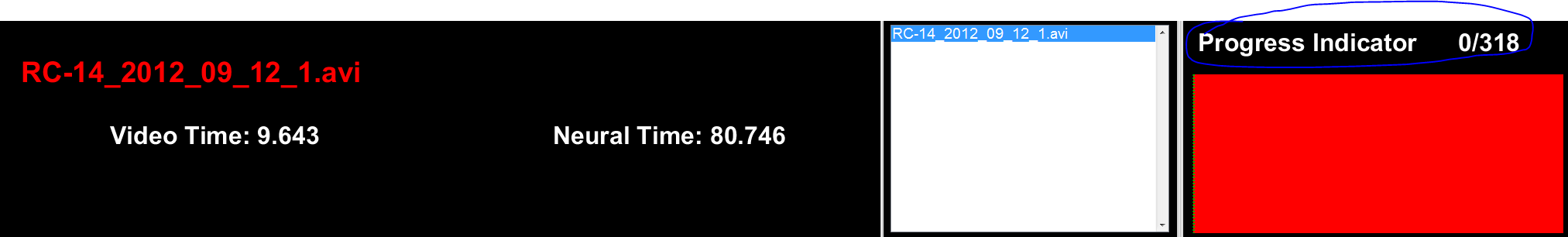

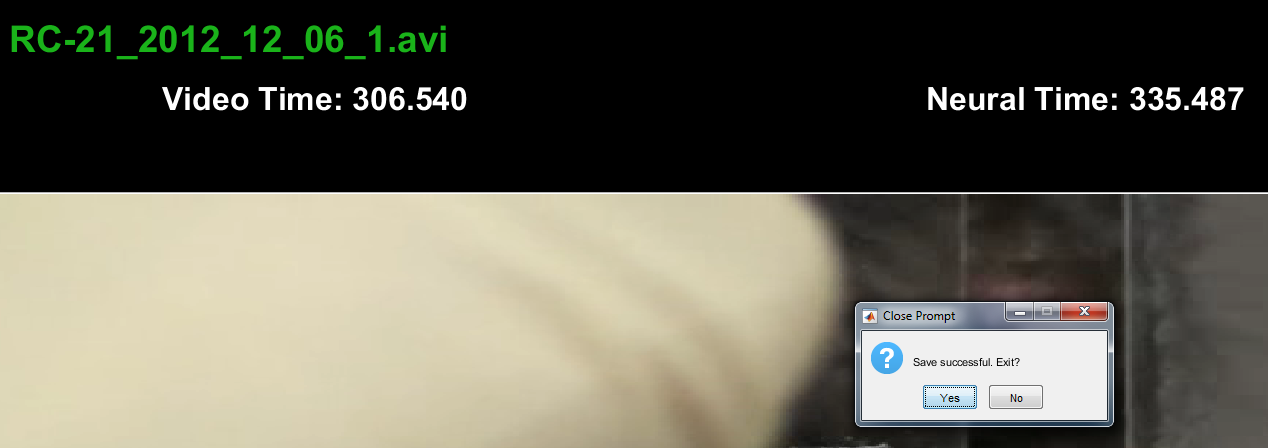

alignVideo HUD

Figure 3: HUD. This region simply shows the name of the currently selected video, the time with respect to the start of the video (Video Time, seconds), and the time with respect to the start of the neurophysiological recording (Neural Time, seconds). The window on the right could be used in case there are multiple videos for a given neural recording, but in practice this hasn't been used.

Figure 4: Save Status. Once you have saved the alignment offset (alt + s), the file name will turn green and the GUI will prompt you to exit.

alignVideo General Strategy

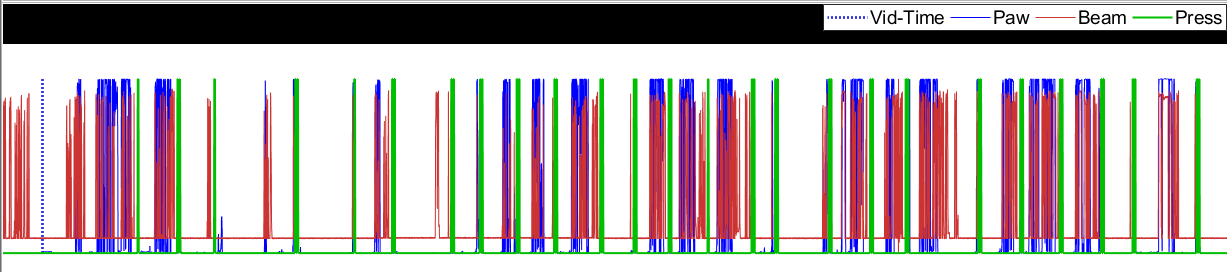

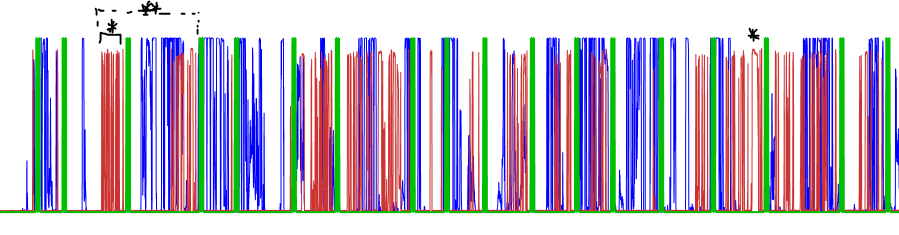

This alignment technique works on the assumption that basically most of the time we see the rat's arm, he is reaching for a pellet or reaching out of the box. So correlating the two time-series gets us a good approximation, and then it is fine-tuned by matching the video image as accurately as possible (within the framerate precision):

- Just try to match up the red and blue lines as best as possible by clicking the red series and then moving the mouse left or right. Click the axis again to "drop" it.

- Zoom in (numpad +) for fine-tuning. When zoomed in, you want to see how the relative timing of the video matches with the current time of the video and beam break data given the current alignment.

- Check several reaches as a sanity-check. Remember, this is only as good as the video frame-rate precision, so it doesn't have to be 100% perfect (there will be some jitter due to the video device sampling and codecs used).

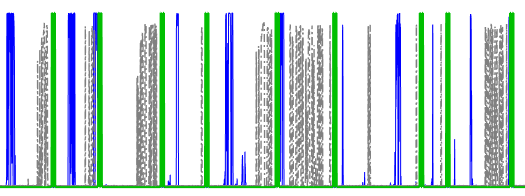

alignVideo Example

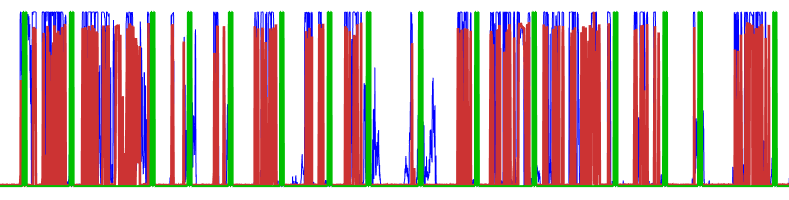

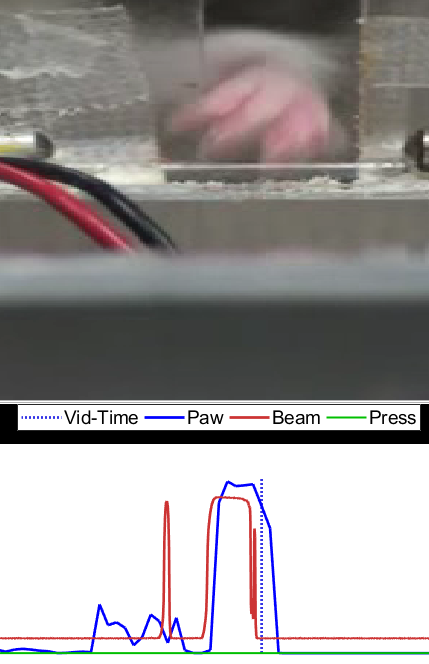

Figure 5: Good alignment guess. In this case, the correlation algorithm worked pretty well and the "trains" appear to be aligned fairly well. Recommend going straight to step 2.

Figure 6: Bad alignment guess. Something went wrong with the correlation algorithm. Note the starred points. You want to grab an idiosyncratic "feature" of the red train to try and have the best ability to line it up with a similarly shaped point on the blue train. Alternatively, the double-starred point shows where you have two high-frequency "bursts" near each other, which tends to be an easier thing to match up while dragging the series against one another.

Figure 7: Bad dragging match. The dot-dashed series is being dragged, but at this point it doesn't really match up well on anything. Notice lots of periods where the blue and dot-dashed series do not overlap.

Figure 8: OK mismatch. Sometimes, the experimenter's hand is in the way etc. so you don't get the paw time-series. So in that case you should be able to see the beam breaks but not have any paw probability time-series since DeepLabCut (DLC) couldn't "see" the paw. In practice, DLC was pretty accurate on detecting the paw presence, so more often than not it is worse to have a lot of blue (paw) series that don't have any matching red series than the other way around. It sort of depends on the idiosyncracies of the rat, though.

Figure 9: Good match. Once things are aligned, click the axis again and it will make the lines bold and they won't follow the mouse any more. Notice how the blue lines have more or less "disappeared" behind the red, indicating that this is a good approximate line-up.

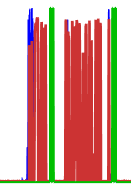

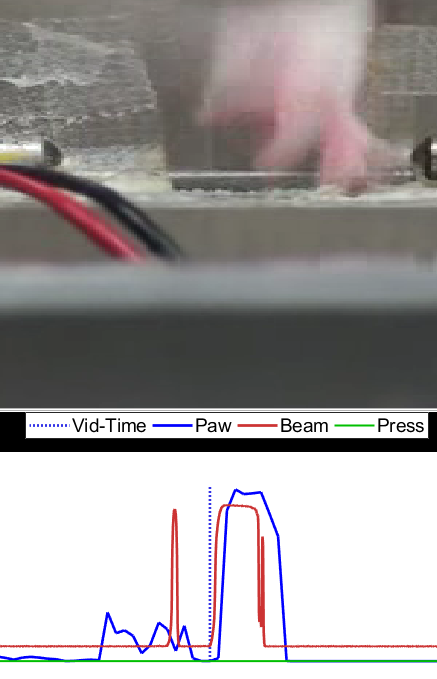

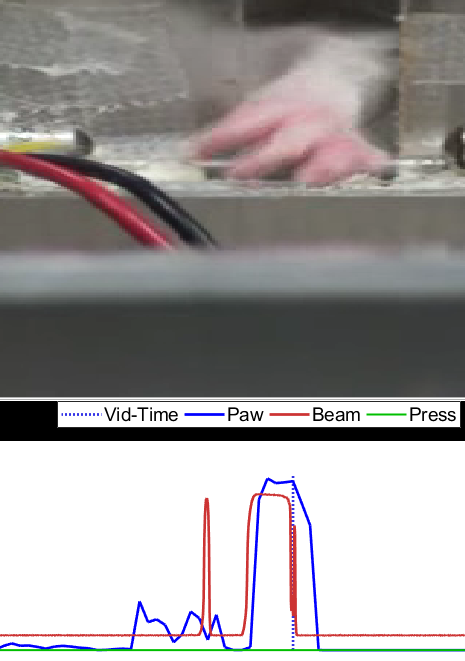

Figure 10a: Fine-tuning. Click the zoomed-out axis above the series to move the video to that time-point. Then zoom in (numpad +). You can zoom back out if this ends up not working (numpad -), or hit spacebar to just play the video and approximately see how it looks. You can also navigate 1 frame forward or backwards using the 'd' and 'a' keys respectively. Here, a point is selected just before the onset of a moderate-length beam break, where the paw was also detected. Notice that the alignment so far is good because the beam is not crossed and we are not crossing it yet in the time-series.

Figure 10b: Fine-tuning. Advancing by 1 frame, the beam is crossed and it is also crossed in the time-series.

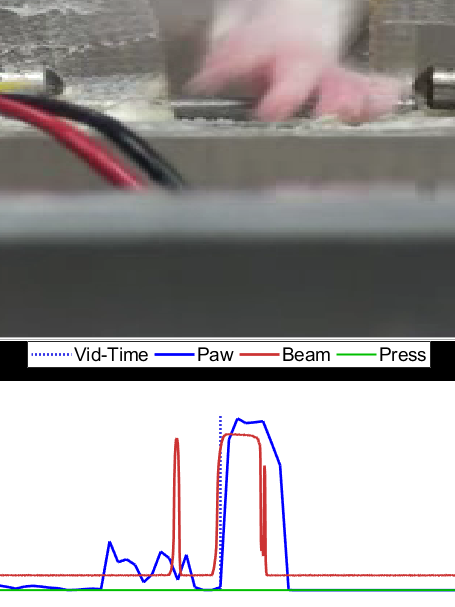

Figure 10c: Fine-tuning. Going to the end of the beam-break, we see that in the last beam frame, the paw still appears to be crossing the beam.

Figure 10d: Fine-tuning. Advancing by 1 frame, the paw has moved off of the frame in the video and the red line indicating the tripping of the beam-break by a high value has returned to low as well. Repeating this process for several beam-breaks at various points throughout the video gives a good indication that the video and neural data are aligned.

alignVideo Hotkeys

- alt + s | Save current offset.

- a | Go back 1 frame.

- leftarrow | Go back 5 frames.

- d | Advance 1 frame.

- rightarrow | Advance 1 frame.

- numpad - | Zoom out on alignment timeline.

- numpad + | Zoom in on alignment timeline.

- spacebar | Play or pause the video (can run slowly; typically faster to navigate by clicking on video alignment timeline).

Video Scoring

scoreVideo Setup

- Put all the video files in one folder and update the variable VID_DIR in scoreVideo.m to reflect that path. Alternatively, if all of the *.avi (video) and *.mat (data) files are kept together, then don't worry about updating VID_DIR. If you plan on running scoreVideo without input arguments, you may want to configure DEF_DIR as well to speed up the file selection UI.

- The *_VideoAlignment.mat file that is output from alignVideo.m is optional; it lets you see the relative neural time compared to the video time, but since all time points are relative to the start of the video it is not necessary for the scoring to run.

- A *_Trials.mat file that can be placed either in the same directory as the videos, or wherever as long as VID_DIR is specified. This data file contains an N x 1 vector of (double) time-stamps (seconds) where candidate trials may occur throughout the video. Because the output from scoreVideo.m is a Matlab Table, each record in the table has a candidate trial that it corresponds to. "Bad" guesses are removed from the table during scoring by pressing the 'delete' key.

scoreVideo Use

File Selection

Overview

HUD

How to Score

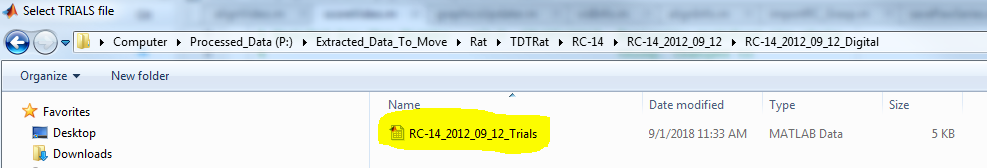

scoreVideo Select File

Figure 1: File selection. If no arguments are specified, select the Trials.mat file from wherever you have put it. After a few steps of processing, generating the interface, and loading the video, the interface should popup. To skip this step, specify the optional ('FNAME', val) argument pair.

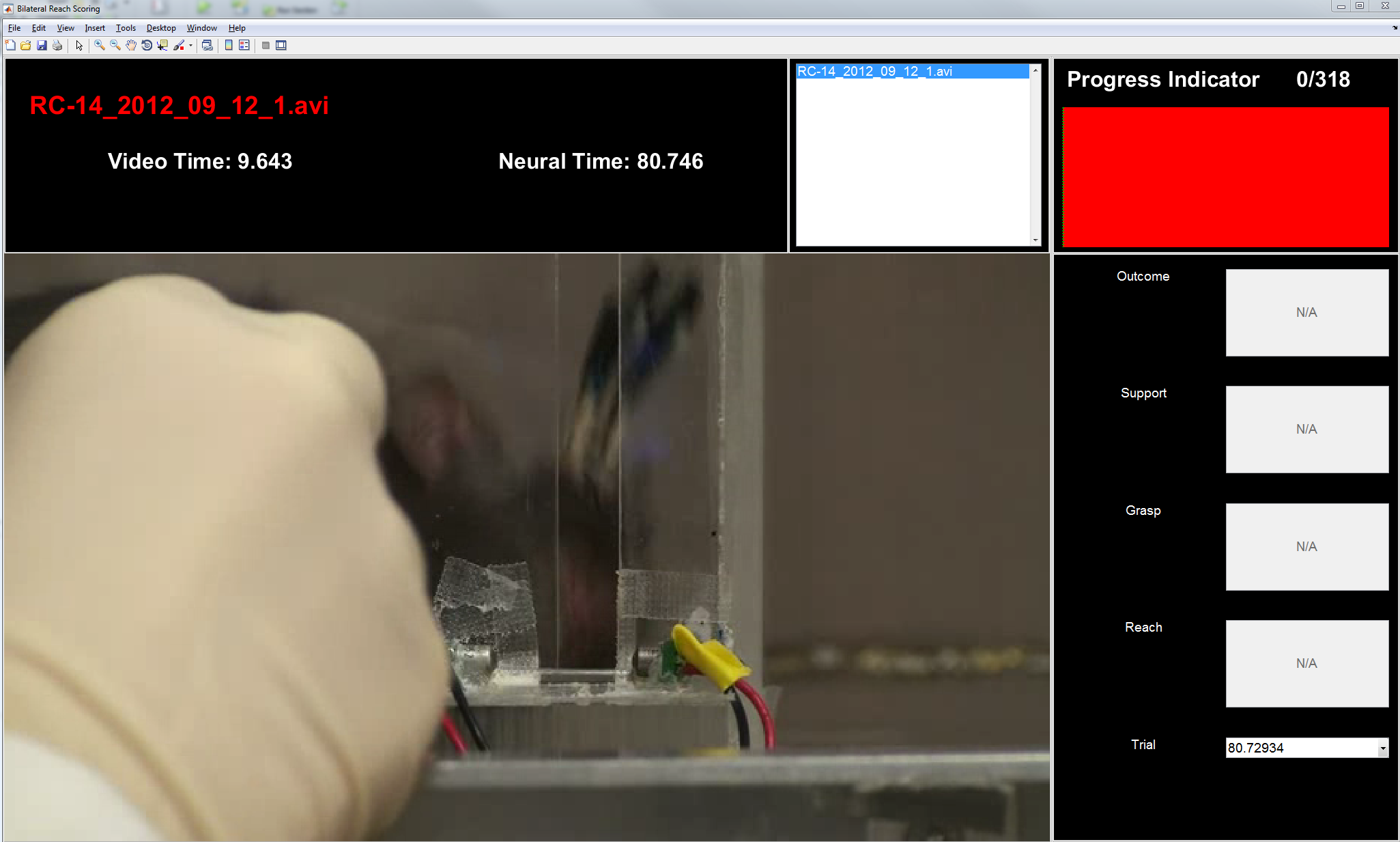

scoreVideo GUI Overview

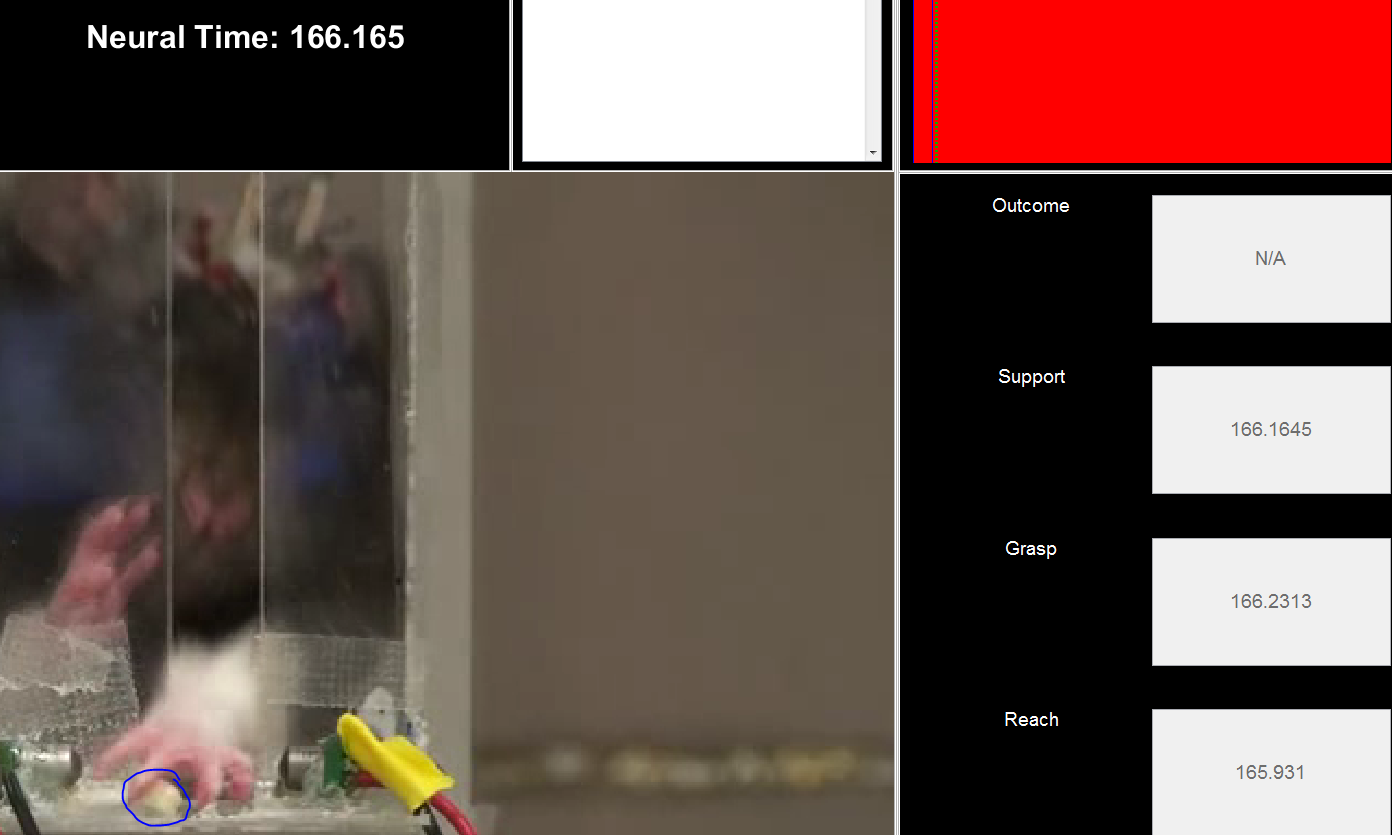

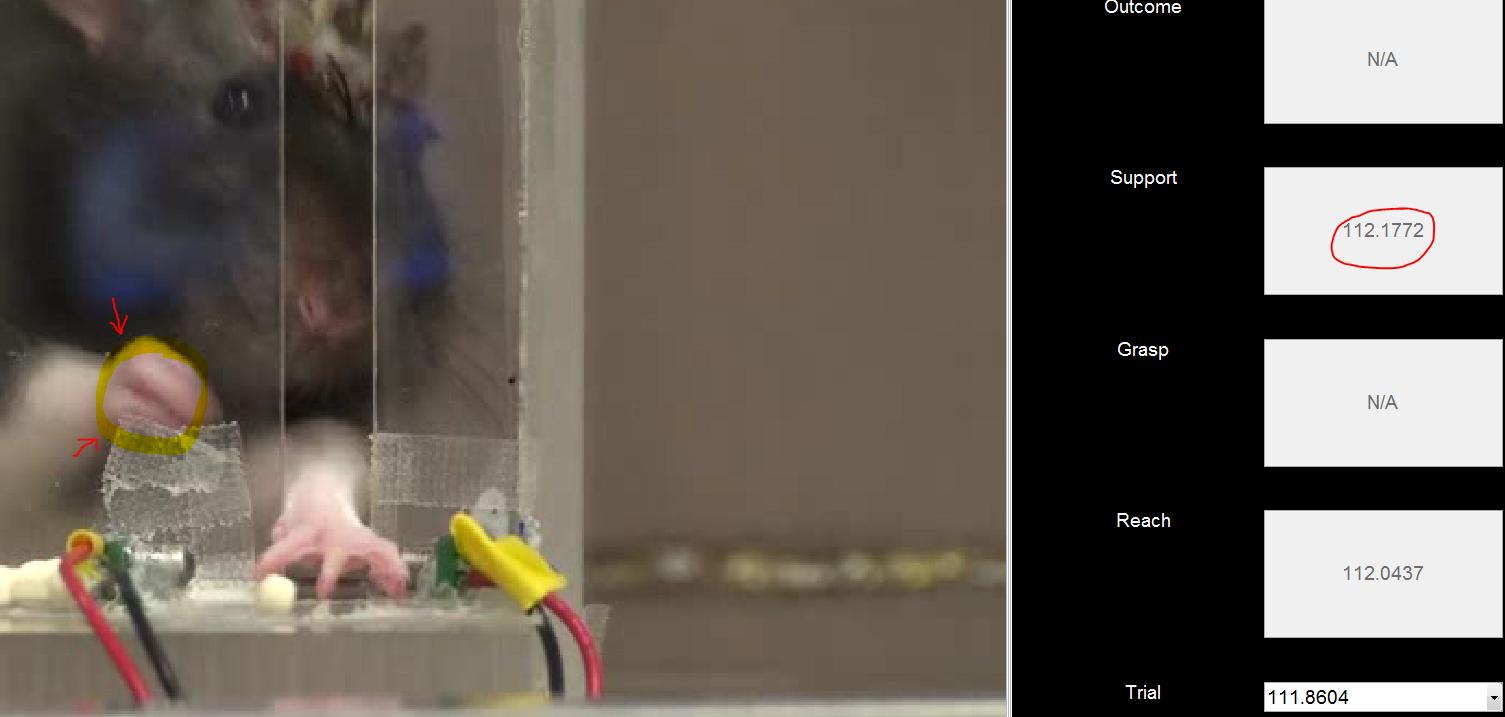

Figure 2: GUI overview. The graphical user interface (GUI) consists of 3 main components: a heads up display (HUD) at the top; the video which is displayed on the left/middle; and a control display for marker times on the right side.

scoreVideo HUD

Figure 3: HUD. This region simply shows the name of the currently selected video, the time with respect to the start of the video (Video Time, seconds), and the time with respect to the start of the neurophysiological recording (Neural Time, seconds); if no alignment has been done, the default is zero offset. The main difference from the alignVideo.m HUD is the right-most part that has a progress indicator that shows the total number of trials to score and the current trial being scored. As invalid trials are removed (delete key), the total number of trials will decrease. When all fields (Reach, Grasp, Support, and Outcome) have been filled for a given trial, the corresponding segment of the tracker image will change from red to blue. Continuing a previously-scored video should fill the bar with your previous progress and move you to the next unscored trial, so it's fine to save (alt + s) in the middle and finish later.

scoreVideo Defining Events

Reach

Grasp

Support

Outcome

Deletion

Consistency in the alignment event definitions is the most important part of the behavioral scoring procedure.

Reach

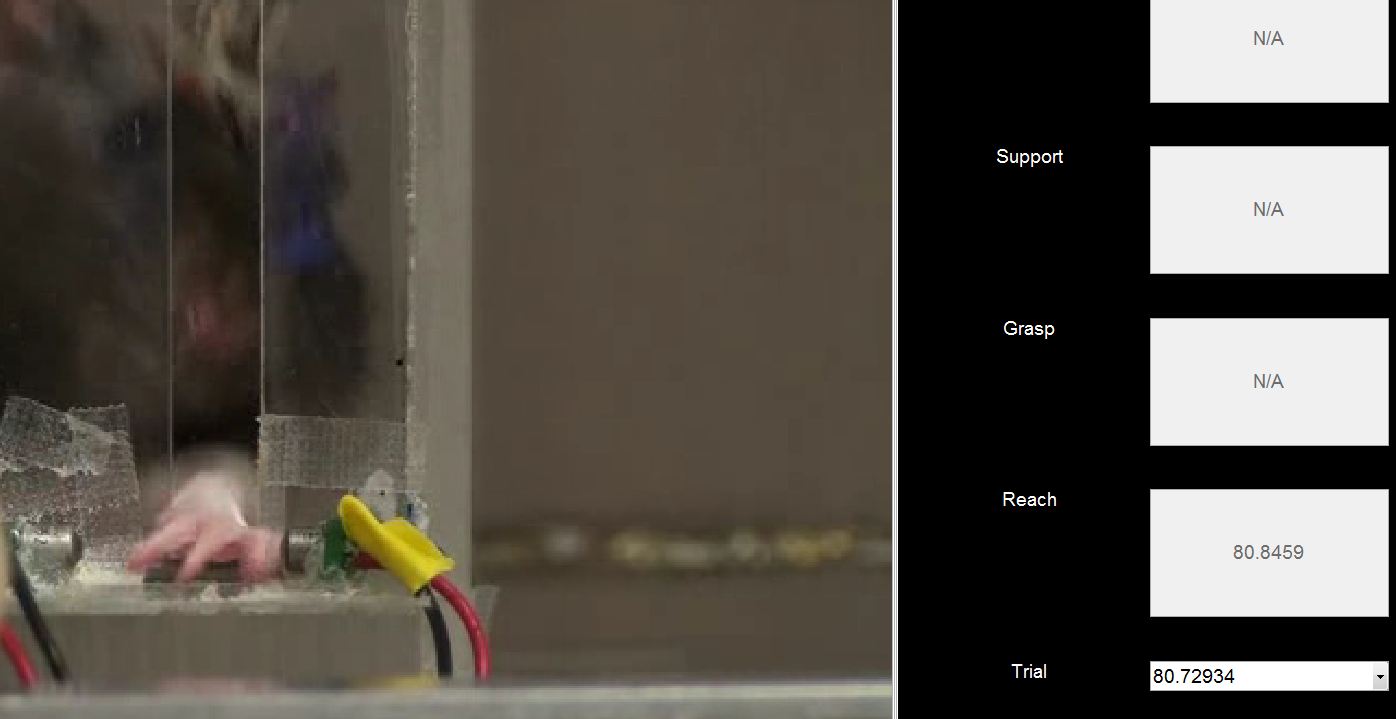

This is the reach onset time. We are defining it as the first frame in which the digits cross the box opening. It is similar to the digits-to-midline.

Figure 4: Bad Reach. Pressing r sets the reach onset time. Pressing it again on the same frame unsets the reach time. In this example, he is reaching but no pellet is present; when this happens he does not close his paw, so it is not considered a complete trial and thus excluded (delete key) from further analysis.

Figure 5: Not-a-grasp. This is a typical posture when a reach is performed without a grasp. This type of behavior is discarded.

Figure 6: Good Reach. Here, he is just crossing the plane of the box opening, and there is a pellet present.

Grasp

This is the grasp onset time. We are defining it as the first frame in which the digits close around the food pellet. It is the easiest phase of behavior to identify in this experimental setup, and provides the most consistent neurophysiological alignment landmark for behavior. Trials need both a visible reach and grasp in order to be considered for further analysis.

Successful Example

Figure 7a: Successful Grasp - arpeggio. We aren't officially looking for arpeggio, but basically just before he closes his paw, the digits will splay out like this.

Figure 7b: Successful Grasp - closing. His paw closes fully around the pellet. This is the frame that gets scored as grasp onset (hotkey g).

Figure 7c: Successful Grasp - retrieval. The forelimb supinates as he retrieves the pellet successfully. Typical behavior is to bring the pellet directly to the mouth, with the other forelimb coming over to help hold it.

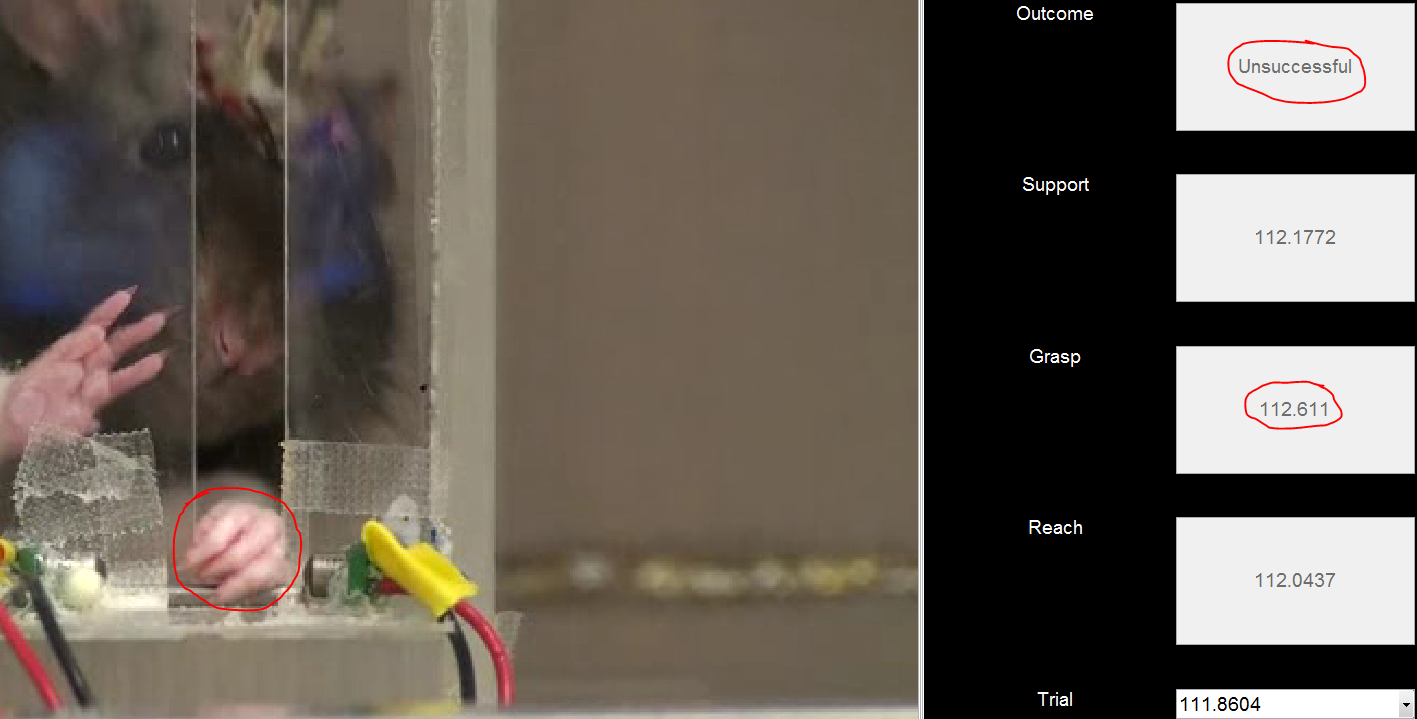

Unsuccessful Example

Figure 8a: Unsuccessful Grasp. Here, he has attempted to retrieve the pellet (left), but was unsuccessful as it has popped out. He still closed his paw, so this is considered as a grasping trial.

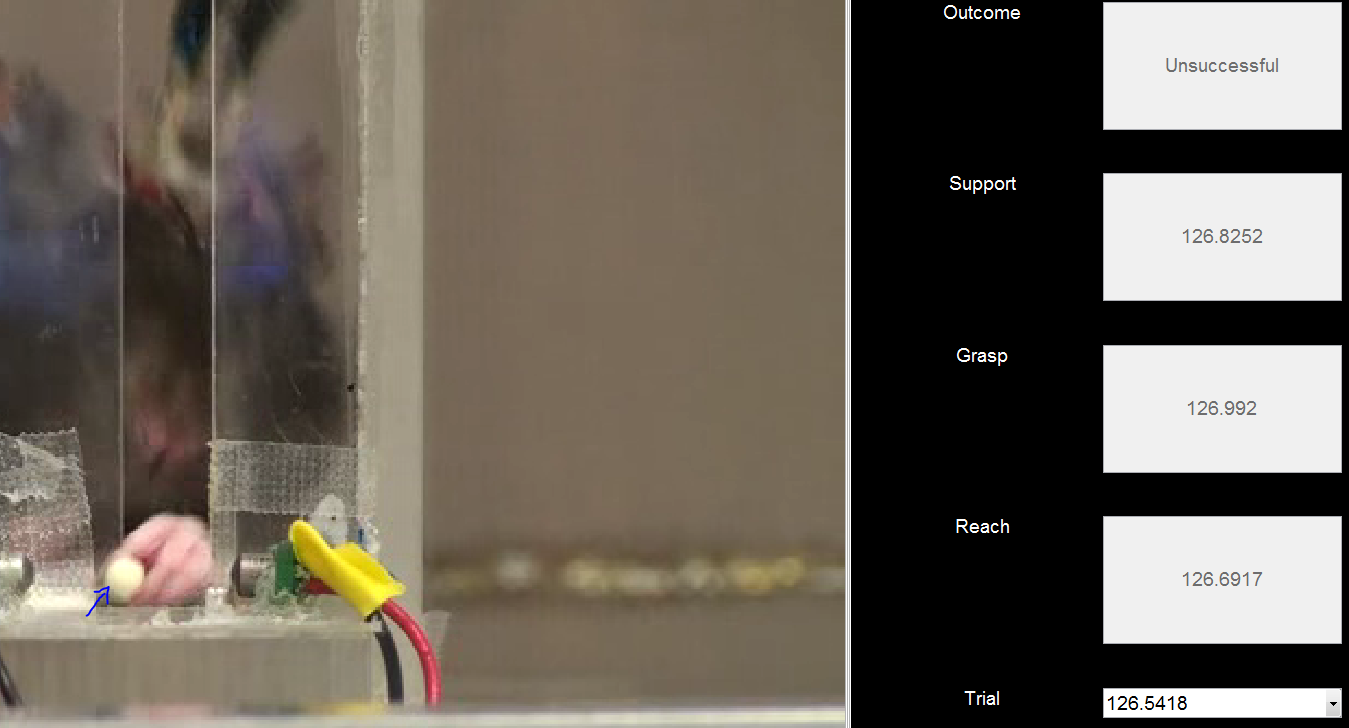

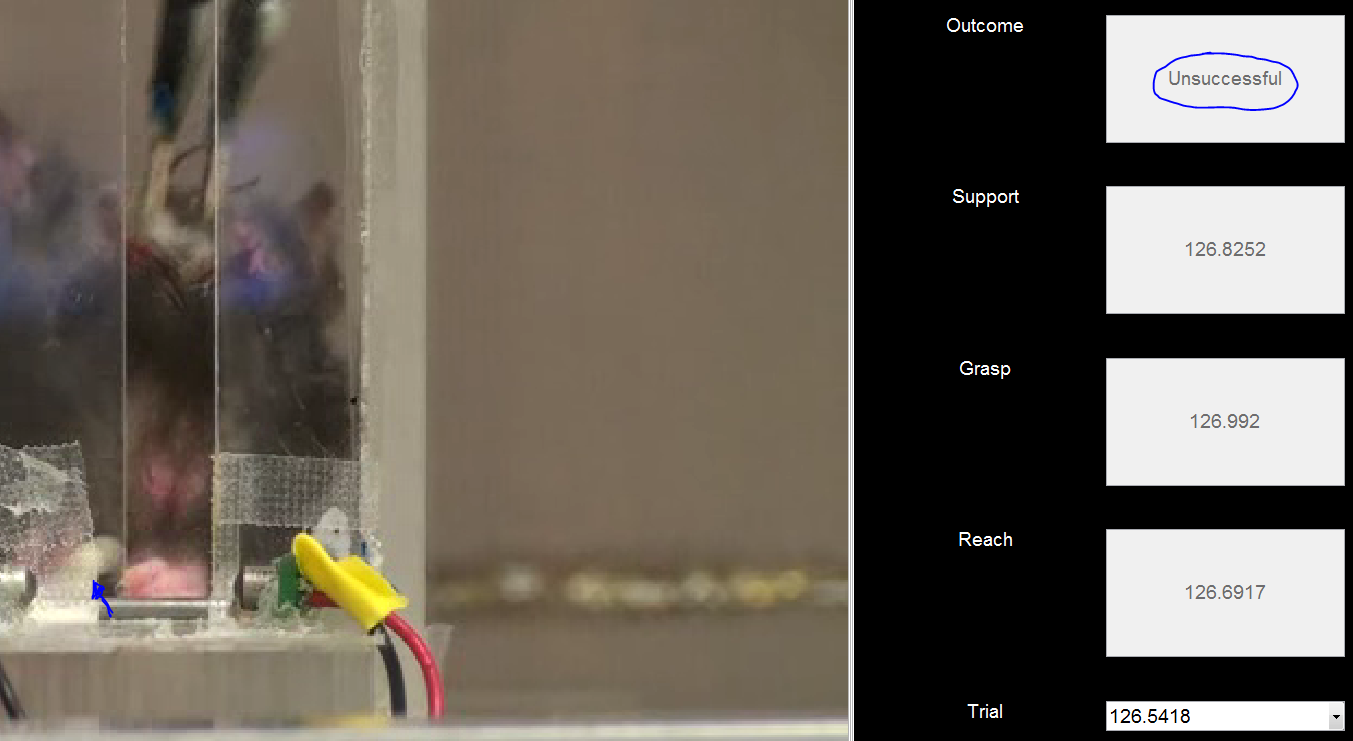

Figure 8b: Unsuccessful Grasp - closing. A common failure mode is the lack of fine motor control in the digits, particularly in injured rats. In this case, the pellet just got wedged between his digits but he did not actually fully close the digits around it.

Figure 8c: Unsuccessful Grasp - retrieval. When the pellet is retrieved as in 8b a small bar prevents the full retrieval of the pellet into the behavioral box. This results in the pellet popping out of the paw (blue arrow).

Support

This is the support onset time. It is fairly approximate, since the supporting limb is inside the behavioral box and often partially obscured from view. This is primarily scored to give an indication of the number of trials in which the inappropriate forelimb was grossly active during the trial.

Figure 9: Support limb activity. As soon as the other forelimb is seen actively moving (particularly pressing against the glass or mirroring the movements of the retrieving limb), the support marker is placed (hotkey b). If no activity of the other forelimb is observed for the duration of the trial, this is indicated by marking the support time as inf (hotkey v).

Outcome

This is the functional result of the trial, in terms of whether the pellet was received successfully or unsuccessfully. Trials in which the pellet was retrieved but not brought to the mouth for ingestion are considered unsuccessful because they don't represent a functionally complete behavior. See the Grasp section for examples of differences between successful and unsuccessful retrievals.

scoreVideo Hotkeys

- alt + s | Save current offset.

- a | Go back 1 frame.

- d | Advance 1 frame.

- q | Mark current trial as (rat's) left forelimb.

- alt + q | Mark all trials as (rat's) left forelimb.

- e | Mark current trial as (rat's) right forelimb.

- alt + e| Mark all trials as (rat's) right forelimb.

- t | Mark/unmark current frame as reach. Removes the marker if the same frame is selected twice.

- r | Set current trial as not having a reach. (see hotkey v)

- g | Mark/unmark current frame as grasp. Removes the marker if the same frame is selected twice.

- f | Set current trial as not having a grasp. (see hotkey v)

- b | Mark/unmark current frame as "both" (support). Removes the marker if the same frame is selected twice.

- v | Set current trial as not having a support hand. This can be undone by pressing v again, or by specifying the support frame by pressing 'b'. This is basically so that the progress tracker works properly (and downstream data doesn't have to be cleaned).

- w | Mark current trial as successful.

- x | Mark current trial as unsuccessful.

- numpad0-9 | Mark the number of pellets in the frame, including the pellet in front of rat

- numpad+ or numpad- | Mark presence (+) or absence (-) of pellet in front of rat.

- leftarrow | Go to the previous alignment trial. Can also be selected from dropdown list.

- rightarrow | Go to the next alignment trial. Can also be selected from dropdown list.

- delete | Remove this trial. (Careful; scoring has to be restarted if you want to refresh a removed trial, currently). This should be done in instances where the proposed trial, which is based on the paw probability time-series, does not correspond to an actual reaching event (and in many cases, this means a reach with NO GRASP). You have to check that subsequent trials are not corresponding to the same scored reach frames, the GUI does not check that for you currently.

- spacebar | Play or pause the video (can run slowly; typically faster to navigate by clicking on video alignment timeline).